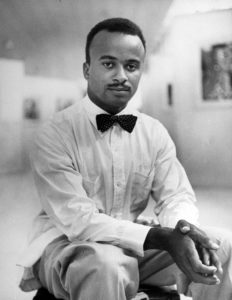

Michael Cortor reflects on his father, Eldzier Cortor

ELDZIER CORTOR (1916-2015)

Black Art Auction is deeply grateful to share some reflections from Michael Cortor, the artist’s son, on his father’s passion for the process of art.

A day doesn’t go by that I don’t think about my father (as well as my mother). You know him as the artist, one of the few who could claim membership in both the Chicago and Harlem Renaissance. I was very fortunate enough to be surrounded by art growing up as well as experienced a true racial diversity living in a modest household on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. My father had a very long career and outlived all of his contemporaries. His passion was art and yet at the age of ninety-three he took a pause and devoted himself to caring for my mother who was terminally ill. After her passing, two years later, my father returned to his passion of art and completed thirteen paintings (a couple of them quite large) and had two unfinished works. His very last signed painting was a painting that he based on one of his L’Abbatoire etchings.

My father did much of his printing at Bob Blackburn’s Print Studio. He began printing at the studio in the late 1960’s and continued up until 2000 (when Bob Blackburn passed away). When I think about when he was working on the “Jewels “ series he was septuagenarian, an age when most people settle down. Of course when printing the entire series, my father used a printer, but he closely monitored the process and all of the elements used and the preliminary test and proof prints were done by my father by himself.

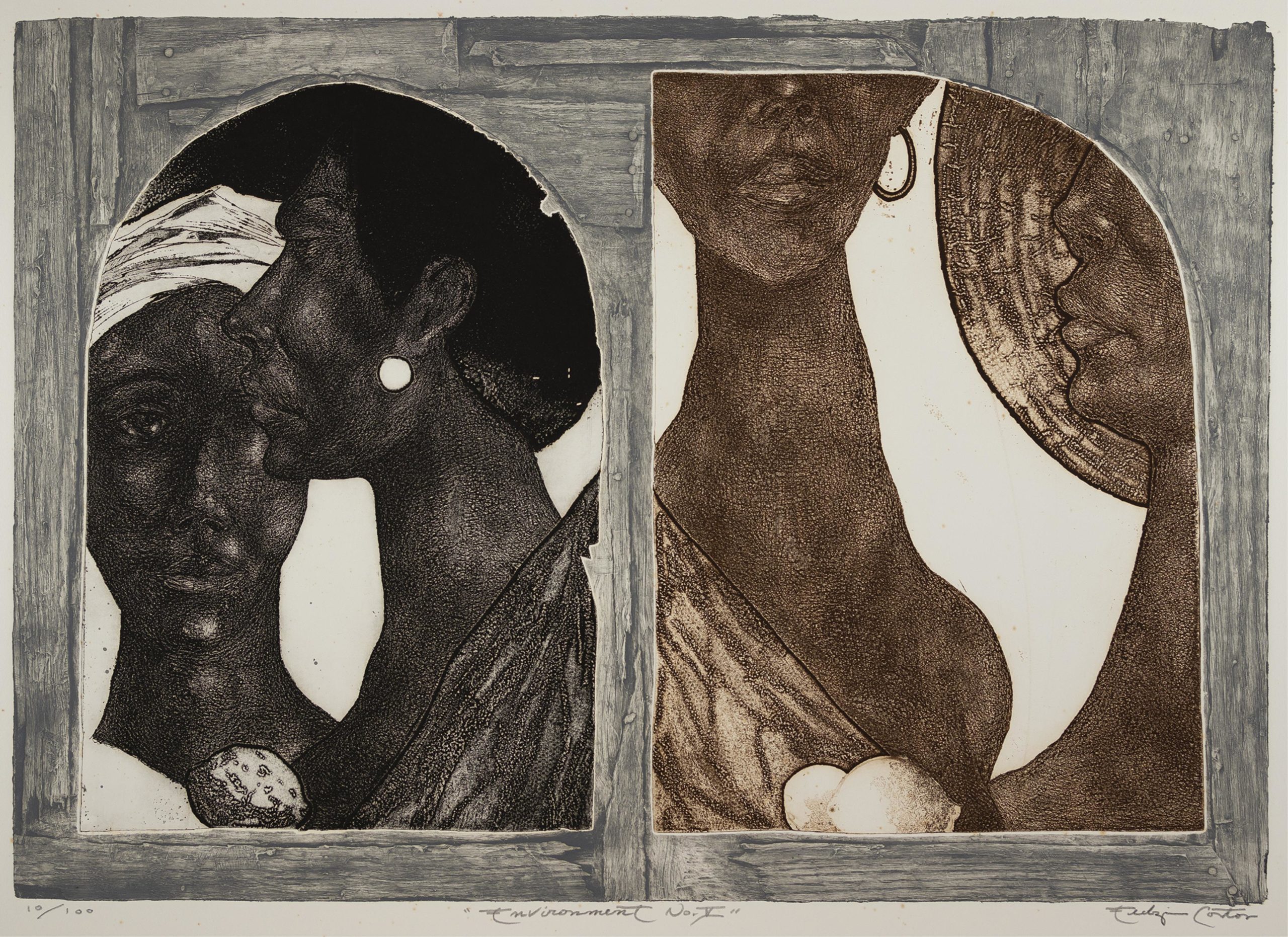

Regarding the “Jewels” print, my father, did seven different versions and used a variety of techniques as well as a number of items used in the process. He used the mezzotint technique on the print plate for the figure and many of the key elements. The technique involves completely covering a plate with a series of closely knit cross hatched lines (which were produced by hand using a tool called a rocker). The plate then was inked and run through the press which produced an intense black (or what ever color ink used). My father would use tools such as a burnisher and files to carve out images. He controlled the highlights and shadowing of the figures and other elements that he wanted in his finished product. To further enhance the image, my father would cut out sections of the plate as well as bore holes in the plate. The result would dramatize the contrast and make the figures stand out. My father would use other plates, where he carefully sectioned off areas and used the process of etching and aquatint, in the printing process those sectioned off areas had various colored inks applied directly to them. He did not hand color those “Jewels” prints. In addition my father also used shellacked pieces of cardboard which were carefully places in areas in which he wanted show relief, usually in the border areas. The printing process was very involved and required multiple steps.

These photos from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, illustrate the labor intensive, multi-step process, Cortor undertook to produce just one print of his Jewels/Theme III. His Jewels Series contained seven different images of his graceful women encased in sharply cut gemstones. (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/729979)

One of the country’s most respected African American artists, Cortor spent years studying diasporan peoples in the American South and the Caribbean, and, over the years, amalgamated various aspects of women of the African Diaspora into his prototypical black female. Eldzier Cortor was one of the first black male artists to explore the beauty and intensity of black womanhood. Sensuous and melancholy women of color inhabit Cotor’s intimate spaces. Seated in a stylized interior, the elongated, gracefully introspective woman of [Jewels/Theme V] represents Cortor’s idealized black female.

Adrienne L. Childs (object entries), Narratives of African American Art and Identity: The David C. Driskell Collection, p. 138.

The print “Environment” used a different approach. My father used two separate zinc plates that involved the etching process and he inked them separately (one using a black toned ink and the other a sepia toned ink). The plates were positioned in a handmade structure (which my father referred to as a “cradle”). The wooden structure had a look that made it seem to be made of planks that were nailed. My father used a viscosity method applying a silver/gray toned ink directly to the structure. With viscosity method, my father was able to enhance the details on the wooden cradle. The printing process itself was done through a single pass through the press.

My dad was truly old school. He believed in the process involved. His printing methods couldn’t be easily replicated. Think of the cost factor for copper plates, and being the perfectionist that my dad was, he must have cut up many copper plates if he wasn’t satisfied with the results. Also my father used zinc plates (such as the ones used for the Environment print). The zinc plates are no longer used because of the toxic vapors emitted when exposed to the acid baths. When I think of all the harmful and flammable substances that my dad had in his studio in our residential apartment I shudder. But he lived just two months shy of his centennial, so he definitely had some immunity.

The Bob Blackburn print studio, where my father had worked on his prints, had briefly closed after Blackburn’s passing in 2000. But a printer, who was associated with Bob Blackburn opened another studio Kathy Caraccio Print Studio on 39th Street (in Manhattan’s garment district). She offers classes and has artists use the facility for traditional printing techniques. I took my father to Kathy’s studio in 2014 where he had a chance to supervise the printing of a few prints using his plates. He truly became so involved and I believe that it was his devotion to his work that kept him alive for so long.

The Bob Blackburn print studio, where my father had worked on his prints, had briefly closed after Blackburn’s passing in 2000. But a printer, who was associated with Bob Blackburn opened another studio Kathy Caraccio Print Studio on 39th Street (in Manhattan’s garment district). She offers classes and has artists use the facility for traditional printing techniques. I took my father to Kathy’s studio in 2014 where he had a chance to supervise the printing of a few prints using his plates. He truly became so involved and I believe that it was his devotion to his work that kept him alive for so long.

###

Eldzier Cortor was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1916. His family moved to Chicago in 1917 where Cortor was to play a large role in the Chicago Black Renaissance of the 1930’s and 1940’s. In 1936, he attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and later studied at Chicago’s Institute of Design under Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. He worked

for the WPA Federal Arts Project in the 1930’s and in 1941, co-founded the South Side Community Art Center on South Michigan Avenue.

After winning two successive Rosenwald Grants, he traveled to the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas. It was here that he began to paint the women of the Gullah community as the archetype of African American culture, with their long, elegant necks and colorful head scarves. He focused on “classical composition”, making his figures resemble African sculpture. In 1946, LIFE magazine published one of these semi-nude female figures.

In 1949, Cortor received a Guggenheim Fellowship and traveled to the West Indies to paint in Jamaica and Cuba before settling in Haiti for two

years. There he taught classes at the Centre d’Art in Port au Prince. Cortor worked up until his death in 2015 at the age of 99.

Recent exhibitions of his work have been held at the South Side Community Art Center in 2014; Eldzier Cortor Coming Home, an exhibition of prints, was held at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston held a joint exhibition of the works of Cortor and John Wilson in 2017. His work is found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Howard University.